I was fifteen when a good friend loaned me his battered copy of John Varley’s novel Wizard. At that point in my life, I was the only girl running with an all-male group of nerds who were obsessed with computers and science fiction. Because my friends were mostly guys, I’d started to wonder if there was something kind of weird about my gender, and maybe my sexuality too. But I wasn’t sure what that meant.

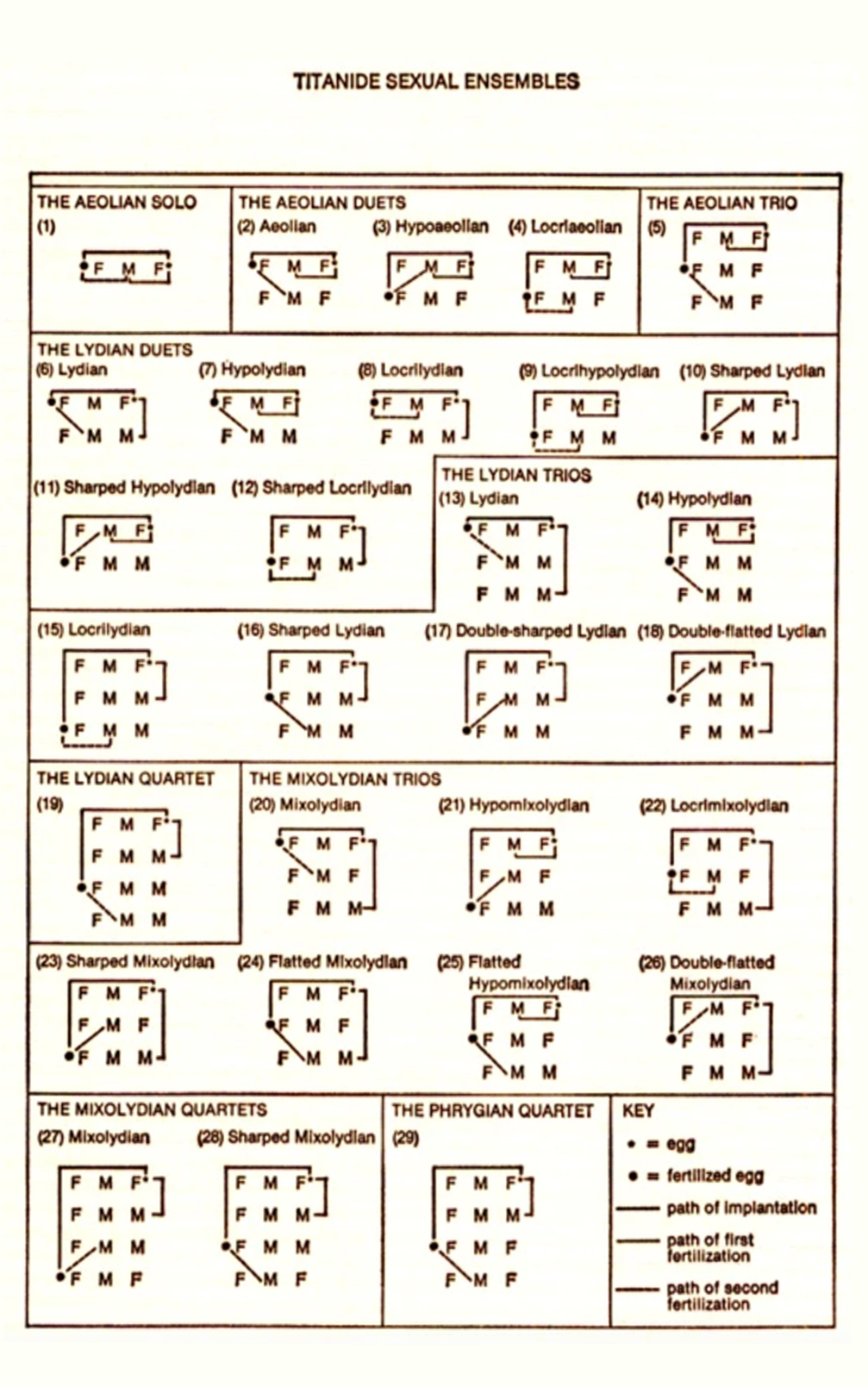

And then I leafed through Wizard. In the section after the title page, where fantasy novels have maps, Varley had a complicated chart of all the sexual positions possible for his aliens, the Titanides, who possessed three sets of genitals. Every year, the Titanides competed for the best sexual positions, and the winners were allowed to reproduce. As I looked over the little boxes full of circles and arrows indicating group sex, solo sex, gay sex, and whatever-the-hell sex, I felt seen for the first time.

The people in this book could be anything–any gender, any sexual configuration. And they didn’t reproduce unless they really, really wanted to. Plus, did I mention that they were all centaurs, created by a benevolent AI who was also a gigantic artificial ecosystem in orbit around Saturn? Yeah. So that was cool.

Around that same time, I also started to get interested in science books written for adults. Basically I wanted the factual version of what I’d gotten out of Varley’s alien sex space opera. At a local mall bookstore, I discovered Alfred Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Sheri Hite’s The Hite Report: A Nationwide Study of Female Sexuality, and of course Nancy Friday’s books of sexual fantasies, My Secret Garden, helpfully organized into an elaborate taxonomy of fetishes, orientations, and genders. I was especially fond of the detailed subcategories in all these books, which reminded me of that chart from Wizard. They turned sexuality into an ordinary part of human life that we could study, as opposed to some obfuscated blob of moral imperatives.

The more I read, the more I was reassured that humans were like Varley’s Titanides, with hundreds preferences that changed all the time. In the long lists of sexual types, subtypes, and paratypes, I saw myself and my friends. I understood, for the first time, that sexuality could be described with zillions of options instead of just one or two. These options were shaped by people’s cultures and racial backgrounds, too. Humans have many identities that overlap. I tried a lot of different options, figuring out what fit for me.

As I grew older, however, I realized that there was a dark side to all this labeling and scientific rationalization of sex and gender. These categories could be used to stigmatize us, to deny us jobs and separate us from our families. Some doctors call minority desires “mental illnesses;” many queers and kinky people have been institutionalized to “cure” them of their preferences. Various forms of romance have been acknowledged, only to be forbidden. In the US, interracial and queer marriage were illegal within living memory, and marriage to more than one person is still unlawful.

Being seen isn’t the same thing as being set free.

Buy the Book

The Future of Another Timeline

Which brings me back to science fiction. Like most people whose identities don’t fit neatly into one of the half-dozen widely accepted categories, I spend an inordinate amount of time trying to fit in. I flatten my gills against my neck, tuck in my tail, and try not to reveal my metal endoskeleton in public. I worry that someone will decide to snip off my antennas to “teach me a lesson.” It’s easier to describe this in the language of science fiction; I can reveal my truth, but dodge the world’s dangerous judgment.

That’s why I find myself drawn to stories about identity that are so complex they require spreadsheets. In work by people like JY Yang, Rivers Solomon, RB Lemberg, NK Jemisin, and Becky Chambers, I see glimmers of worlds where people find love that defies easy categorization. I write those stories, too. But my pleasure is always tempered by the knowledge that there’s a difference between the taxonomies we draw up for ourselves, and the ones that hostile outsiders make to contain us. I fell in love with Varley’s Titanide sex chart long ago because it was a map of possible pleasures, made to light the way for others who aren’t sure where love might be found. Too often, though, politicians, moralists, and scientists name us in order to identify abominations whose lives must be ended.

My point is that I need science fiction to survive. It gets exhausting making myself legible to people who didn’t read the scientific tomes and appendices full of data necessary to understand the choices I’ve made. But in the mutant palace of science fiction, I describe myself and the space I inhabit. One day, maybe, the identities we choose for ourselves will not be used against us. Until then, I will see you in my imaginary democracy, full of living beings you can barely imagine, each contributing care and love to the best of their ability.

Annalee Newitz is an American journalist, editor, and author of fiction and nonfiction. They are the recipient of a Knight Science Journalism Fellowship from MIT, and have written for Popular Science, The New Yorker, and the Washington Post. They founded the science fiction website io9 and served as Editor-in-Chief from 2008–2015, and then became Editor-in-Chief at Gizmodo and Tech Culture Editor at Ars Technica. Their book Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction was nominated for the LA Times Book Prize in science. Their first novel, Autonomous, won a Lambda award, and their latest book The Future of Another Timeline is available now from Tor Books.

Mr. Varley’s story “Options”, which highlights the ease of sex reassignment surgery in his Eight Worlds universe, really made me think about the meaning of “trans” in “transgender”. The protagonist (“Cleo”) changes (transfer-) gender (“Leo”) but chafes under the cluster of social expectations in the both old and new gender and so decides to drop (transcend-) gender altogether, adopting a name (“Nile”) with no gender markings. So, I often wonder, when we discuss “transgender”, of what we should be thinking or at what should we aim?

@1: The way I think about this is that ‘trans’ is just etymologically ‘across’ or ‘through’: compare ‘trans-Atlantic’ or even ‘transfer’, ‘transmit’, ‘transverse’, etc. ‘Transgender’ is typically used to mean someone whose gender (internal sense of who they are and which categories they belong to) differs from the label that was assigned to them when they were born.

Among the non-binary folks (those who are not male and not female), some call themselves transgender and some don’t. Lots of options here, too. Someone might be bigender (‘both of two options’), pangender (‘all of the above’), genderfluid (‘wibbly-wobbly’), agender (‘none of this gender stuff has ever resonated with me in the slightest’ – Vi Hart has a related video), etc. Or maybe someone is cisgender (as in, the person in charge of sticking a gender label on them at birth happened to guess correctly) but their gender expression shows nonconformity (something other than aligning with the gender roles and conventions) with respect to dress, behaviour, career choices, etc.

Cultures might recognize ‘third genders’, ‘fourth genders’, Two-Spirit individuals (in some Indigenous traditions in the part of the world whose colonial name is North America), and so on. Brains are complex and all at least a little bit different, so gender might have billions of very slightly different manifestations. Some of those fit into whatever boxes their culture happens to provide, some don’t.

There is most emphatically a darker side to labels. And not just gender labels. The ones I personally had to worry about were related to neurology not gender but the principle remains the same. And the danger of getting a false label pinned on you.

I really liked these books, though I started with the second and it was absolutely ages until I read the first one. I never really got the fascination with the Titanides and why anybody would particularly care about their various different configurations and interactions but, reading this, I kind of do now. I suppose things appeared kind of ‘simple’ when I was growing up in as much as nobody ever had conversations about things like this, at least nobody I knew.

More recently as gender is something that has been much more widely discussed I’ve been slightly bemused at the need to squeeze everyone into a category and then demand everyone know all these categories. I couldn’t even categorise myself, let alone recognise and remember what anybody else is. I suppose it’s a advantage of being almost completely unsociable that I don’t really need to say “this is what I am” and find anyone similar, though I acknowledge that many do. Still, I suppose it’s a more interesting world.

This resonates with me today, and put into words many things I have recently been thinking about- and now I need to add to my TBR pile!

Although this will detract from the author’s entirely-valid thesis – and for that, I apologize in advance – the chart and the ‘competition’ weren’t actually about sexual positions per se. Each Titanide had three sets of organs and each egg had to be fertilized twice. The chart shows all the combinations that could produce a fully-fertilized egg. In _Wizard_, that ‘benevolent AI’ added a final step: One particular human was given the awesome, overwhelming, and rather horrifying responsibility of deciding which eggs would actually gestate. There was a huge fair each year when all the Titanides who wanted a child – and I believe it was most of them – would basically set up a display to show who was mating with who to produce this particular potential offspring.

All that being said, _Wizard_ did do some exploration of sexuality. The love between two women is at the center of the book. A male human falls in love with a Titanide and has to deal with the fact that her sexuality doesn’t stop with her fore-organs. Titanides are very casual about hindquarter sex, doing it more or less with anyone they like and with no particular consequence. On the other hand, they are quite serious about reproductive sex. But there’s no indication that they place any significance on the fore-genitals as regards attraction, love, and making babies. In our terms they would all be bisexual, I suppose.

Disclaimer: Although I’ve read Varley’s Titan trilogy several times, it’s been a while and I might have misremembered something.

Hello Dr. Newitz,

Gregory Benford sent me a link to your article, which I read with a great deal of happiness. The idea that my little story helped you begin to think about all the complications of sexuality and gender in some way and begin to come to terms with how it all applied to you … well, I guess just about the best thing an author can hear is “Your book changed my life.” I have heard that a few times, and it always makes me a little nervous, because I didn’t have any great moral goal in mind when I wrote it. I was just telling a story and, like all science fiction writers, trying to come up with something that hadn’t been seen before.

It was a different time in 1980. There was little or no discussion around issues of gender identity. It was a concept that had never really come up yet. I mean, you had boys, and you had girls, and you had perverts, right? The idea of LGBTQ (and whatever other letters are still being debated) was still in the far future.

There have been so many changes to the conversation in almost 40 years that I have not really been able to keep up with it all, though I have tried. When I was in high school, queer was the absolute worst thing a boy could be called, especially in my home state of Texas. A boy had to fight anyone who said that, or become a punching bag. Now I see the word used with pride. That has taken some getting used to!

I am sorry to admit that I am not very current in my reading of contemporary science fiction writers, so I have not seen your work. I think I will remedy that in the time I have left. Anyway, thank you so much for writing this article. You really made my day.

John Varley

Especially since John Varley seems to be reading this thread, I will chime in as another nonbinary person who grew up reading New Wave SF to say that the treatment of gender changes in Steel Beach was absolutely lifechanging for me. Until I read that novel and Nancy Springer’s Larque on the Wing, I had no idea how badly I wanted a world in which body parts and gender identities could be put on and taken off as needed to reflect one’s inner self. It would be years before I connected that yearning to being trans, but you really helped me to understand a part of myself that I might otherwise have found baffling or dismissed as irrelevant. As Annalee says, I felt seen. Thank you.

Aw! You just got fan-boied by John Varley!

Great article, and some equally good commentary.

It’s all a continuum, surely on more than one axis, and I guess I’d put myself somewhere about 90% male—and who knows or should really care about even the 90%, let alone the other 10!

As a cisgender old queer who pines for the invisibility of the ghetto, I relate to this statement in what I’m told is an abnormal way: They name us? They see us, so they name us? Why exactly have we mainstreamed our large community again, if visibility it being used against us via naming-then-shaming?

As of today, I am still ambivalent about this whole exercise in mainstreaming, in being visible to Them. I found my hidey-hole to get away from Them, the religious, the sanctimonious, the prurient and puerile passers of judgment. But no one anywhere ever promised that Identity would be, or make things, easy.

I’m so happy to see that your essay got seen by John Varley. And forwarded by Greg Benford, another giant in our genre. Woot! And thanks for your piece.

Varley is so great that way! People Changing at will when they want to. Father of 2 is the mother of 1….. an old friend of over 25 years is a trans woman and I’ve known her thru the entire process. Our bodies are machines that we live in. Still that bad attitude in there!

the Barbie Murders is interesting that it involves a cult where everyone looks like Barbie, only one of them is a murdererer .

And, my all time favorite, The Phantom Of Kansas, where a murder victim meets her male clone and finds out why she’s been killed so many times.

I’M GLAD TO BRING JOHN INTO THIS… he is indeed a giant we should keep learning from. I did!